In 2000, I was a postgraduate student in neuroscience at UCL when I visited the Millennium Dome exhibition shortly after it opened, with my girlfriend (now my wife). We approached the Dome with curiosity rather than scepticism and were both wowed by the scale, creativity, and ambition of what we found inside.

This post offers a nostalgic look inside the Millennium Dome for those who remember the exhibition, and for anyone curious about what it was like. The photographs I took during that visit serve as a visual reminder of a significant moment in British history, capturing the UK’s aspirations and optimism at the turn of the millennium.

Takeaways:

- The Millennium Dome exhibition (2000) presented a bold, immersive vision of Britain’s future at the turn of the millennium.

- Inside the Millennium Dome, fourteen themed zones explored humanity, work, play, community, and our planet through interactive exhibits.

- The Dome stands as an architectural wonder and a symbol of progress, capturing a distinct moment in British history.

- Though the exhibition lasted only one year, its cultural legacy continues today as The O₂ Arena.

What Was the Millennium Dome Exhibition?

For many Gen Z-ers, the Millennium Dome may mean very little. But for those of us born before 1995, it was the UK’s flagship project to celebrate the year 2000. Built in Greenwich, London, the Dome housed the Millennium Experience—a year-long national exhibition exploring who we were at the turn of the century. And who we hoped to become through art, science, and creativity.

National celebrations of this scale are rare, so when they happen, they invite curiosity. The Millennium Dome exhibition was no exception. It offered millions of visitors the chance to step inside a physical expression of Britain’s ambitions for the future.

Moreover, that vision aligned closely with New Labour’s Cool Britannia ethos—an attempt to rebrand the UK as a modern, innovative, and forward-looking nation. One of the most memorable expressions of this mood was Gerald Scarfe’s satirical sculpture of Prime Minister Tony Blair and the Queen, which I photographed inside the Dome. It captured the UK’s desire to redefine itself at the dawn of a new era, blending confidence with self-mockery.

At the time, Cool Britannia struggled to resonate with the public, criticised for overlooking regional identities and everyday concerns. The Dome itself attracted intense scrutiny over its cost and purpose. Much of which I was unaware of at the time (absorbed instead in my studies). Even so, more than six million people visited the exhibition from January 1, 2000 (when it opened) to December 31, 2000 (when it closed).

We visited on January 14, travelling from Kentish Town to North Greenwich. As we approached, dark clouds loomed over the massive white tent. In hindsight, this view could have been an omen for the storm of controversy that followed the project throughout the year.

What struck me most on first seeing the Dome, however, was its futuristic design. Only later did I learn how deliberately the spaceship-like structure embodied its purpose—celebrating the past, present and future. For example, its 365-metre diameter marks each day of the year; its 52-metre height reflects the weeks; and its twelve yellow masts represent the months.

The Millennium Experience: A Journey Through Time

Once inside the Dome, the scale and colour of the exhibits arranged around its vast perimeter struck us immediately. Playful, strange objects—unlike anything we, or most visitors, had encountered before—filled the space. What surprised us most, however, was how empty it felt. For a national exhibition intended to draw the country together, the silence was hard to ignore.

With hindsight, the criticisms aimed at the exhibition make more sense. One common critique was that it presented a narrow, non-inclusive view of Britishness, which may have alienated parts of the public and contributed to lower-than-expected attendance. This disconnect must have been a shock for the organisers, who hoped the exhibition would unite the nation by offering, as the Queen described in the guidebook we bought that day, “a unique experience and an inspiring vision of life in Britain in the new millennium.“

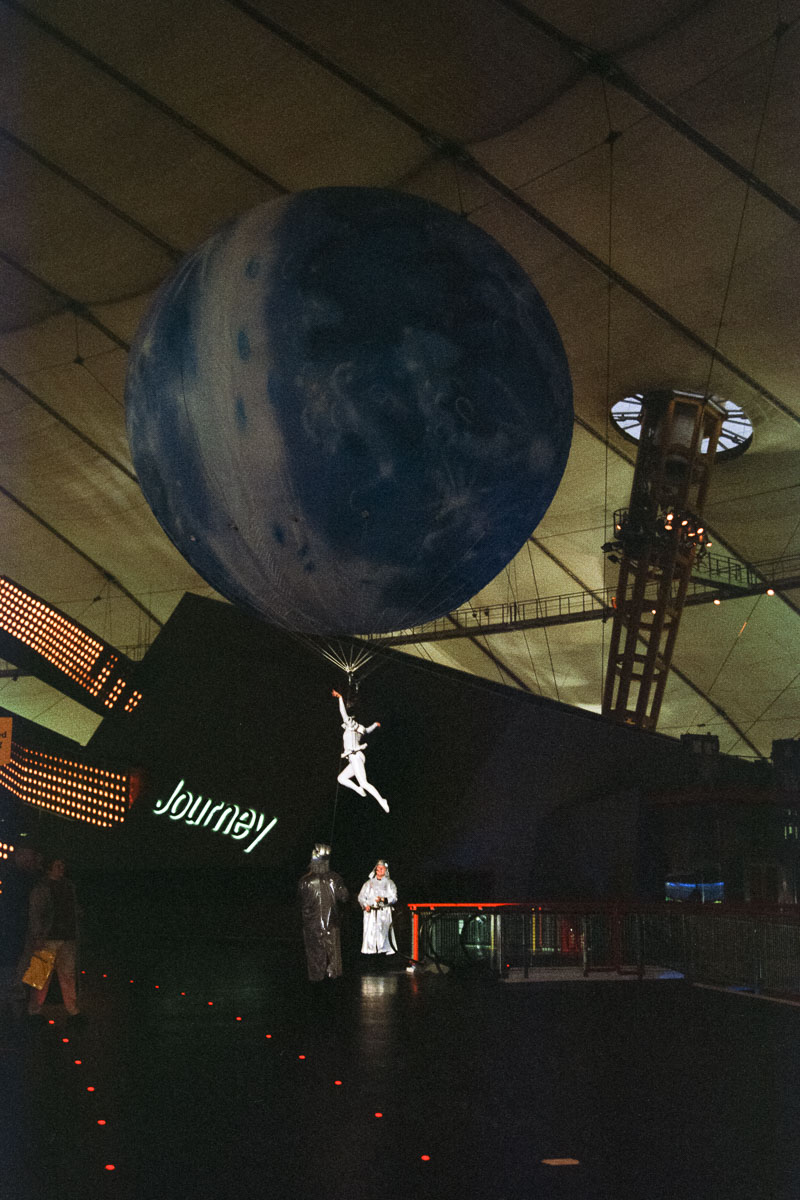

Despite the low crowds, the atmosphere itself was not unwelcoming. Staff greeted us warmly, often dressed in humorous costumes, while performers floated overhead suspended from Earth-patterned balloons. Yet moving through the Dome could feel oddly solitary. The exhibition encouraged individual exploration, which sometimes created a sense of distance from the displays. At moments, it felt like we were watching from the sidelines rather than being part of the experience—standing on the edge of something vast and challenging to grasp all at once.

According to the guidebook, the Millennium Experience comprised fourteen exhibition zones organised around three broad themes, each exploring a different aspect of life. For example:

- Who We Are (Body, Faith, Mind, Self-Portrait)

- What We Do (Work, Learning, Rest, Play, Talk, Money, Journey)

- Where We Live (Shared Ground, Living Island, Home Planet)

Below are photographs I took during my visit, showing exhibits from across all three themes.

Inside the Millennium Dome Exhibition: Exploring the ‘Who We Are’ Theme

This theme explored our identity.

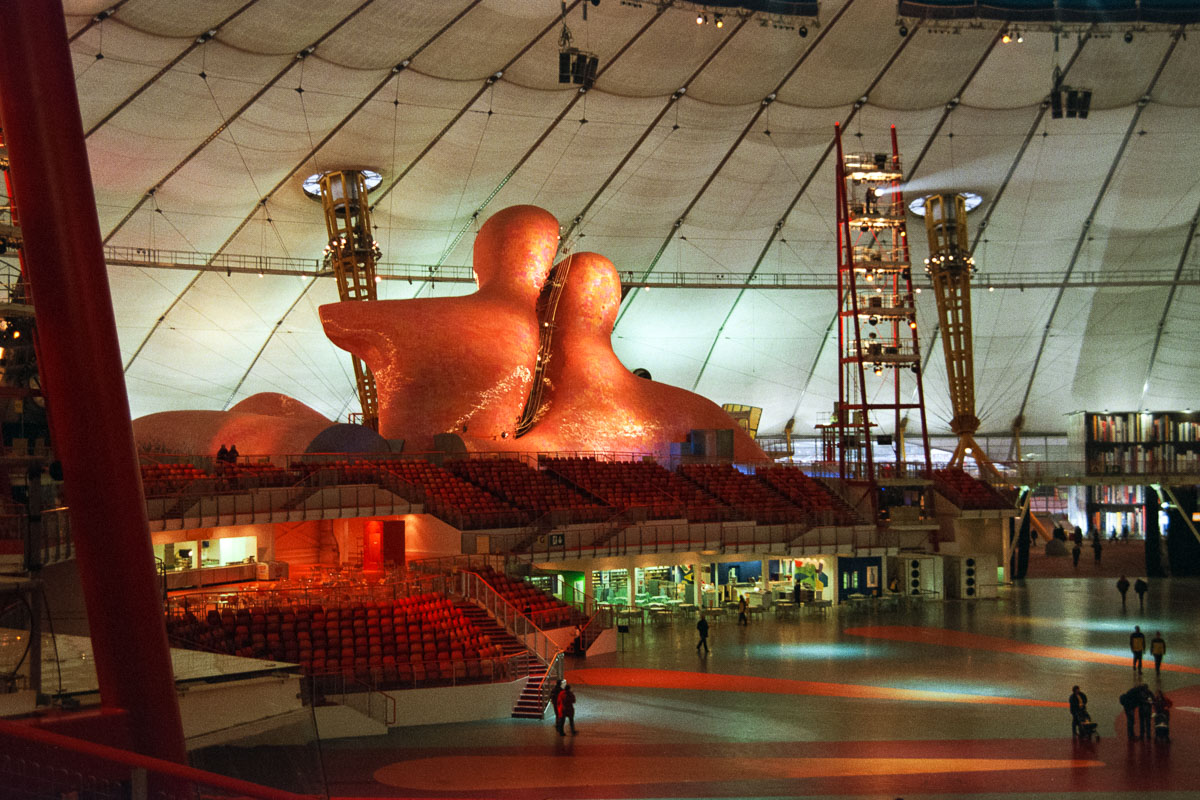

Body Zone: A walk-through anatomical structure shaped like two reclining figures. It was one of the most memorable installations in the Dome. Shimmering with 80,000 lenticular tiles, it invited visitors to experience human biology from within. What stayed with me most, though, was my wife’s reaction. She vividly remembers the unpleasant smell inside the structure—an oddly vivid sensory memory outlasting many of the sights.

Mind Zone: Multimedia installations explored how the brain works—and how easily it can trick us. The exhibits focused on intelligence, perception, illusion, language, and the mind’s untapped potential. Topics I now teach as a psychology lecturer. But looking back, I find it ironic that I took no photographs in this zone. A curious omission, given both my academic background and my tendency to document everything so carefully.

Faith Zone: Tall pillars portrayed key life stages (e.g., Birth, Initiation, Family, Alive & Wonder, Learning, Death, Awakening, Marriage, and Community) through the lens of nine major religions. Moving through this space felt more contemplative than spectacular. Rather than offering answers, it encouraged reflection on life’s universal experiences.

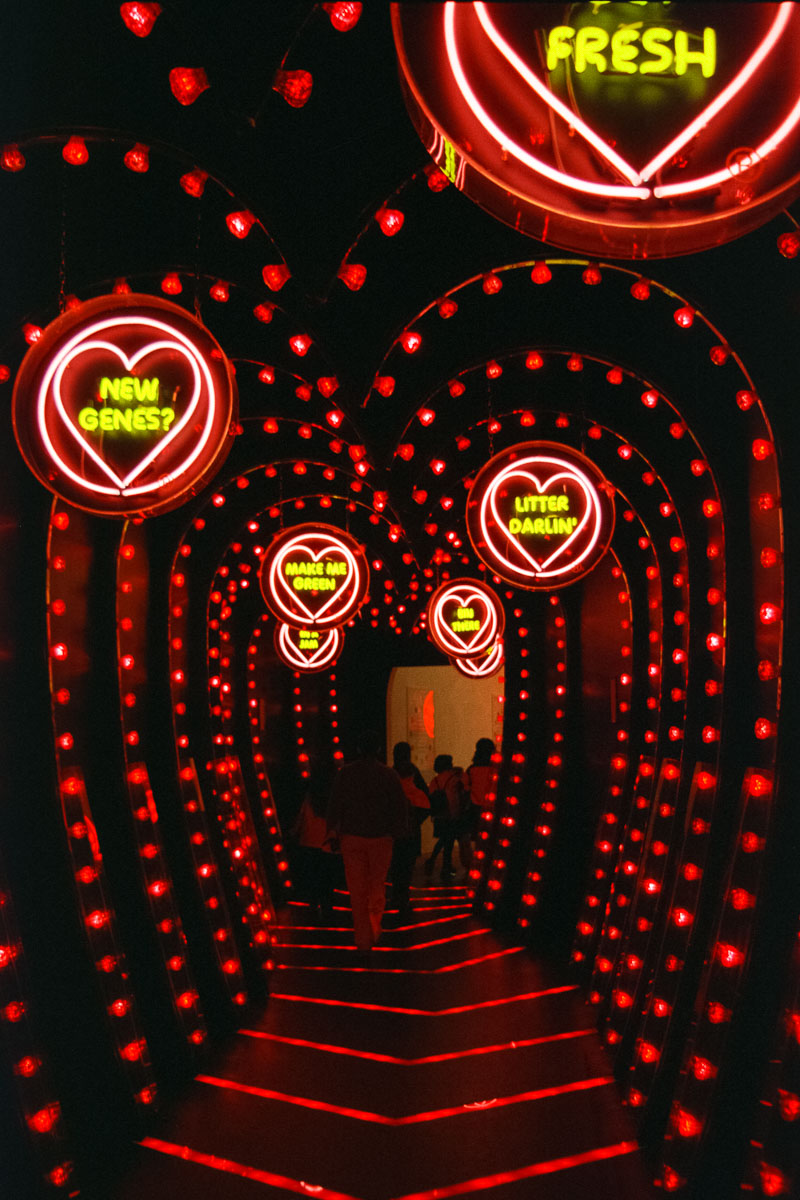

Self-Portrait Zone: Celebrated what it meant to be British in 2000. Over 400 public-submitted images—from a Brown Betty teapot to the Union Jack—rotated around a huge glowing drum, creating a miniature portrait of Britain. But the standout exhibits for me? Grotesque sculptures by political cartoonist Gerald Scarfe. They mocked racism, football hooliganism, and media addiction—sharp, unsettling, and darkly funny. These satirical works feel even more relevant now than they did in 2000.

Inside the Millennium Dome Exhibition: Exploring the ‘What We Do’ Theme

This theme explored human activity.

Work Zone: Interactive displays promoted six core skills for success in the modern workforce—communication, numeracy, problem-solving, IT skills, hand–eye coordination, and teamwork. One of my favourite exhibits was a giant table football game designed to reward collaboration. Taken together, the displays warned against boredom at work, while emphasising the importance of continuous skill development.

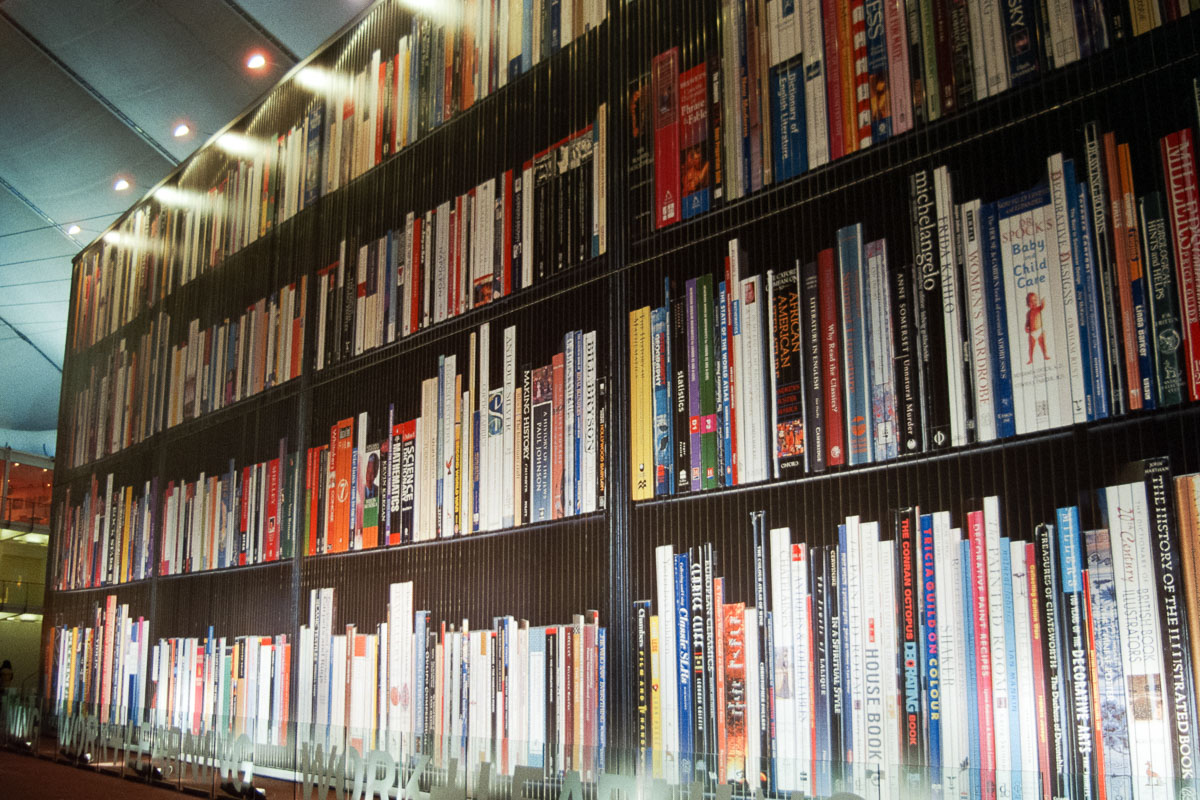

Learning Zone: Immersive experiences—from a school corridor to the surreal Infinite Orchard—celebrated lifelong education as a pathway to new opportunities. What struck me was how this zone resisted the idea of education as something confined to adolescence. Instead, it framed learning as an ongoing pursuit. Particularly vital in a shifting labour market where adaptability, rather than stability, was becoming the norm.

Rest Zone: Calm lighting, ambient soundscapes, and the 1,000-year-long Longplayer composition encouraged visitors to slow down and disengage. At the time, this emphasis on rest felt novel, almost indulgent. But seen from today’s perspective, in an era of constant connectivity and burnout, the zone feels quietly prescient.

Play Zone: From sport and leisure to music, arts, hobbies, and games, this zone foregrounded play as central to creativity, learning, and problem-solving. Reflecting on it now, I’m struck by how strongly it valued real-world play in fostering collaboration and genuine relationships. Qualities we increasingly neglect in today’s digitally dependent, social media-absorbed culture.

Talk Zone: A timeline of communication technologies—from smoke signals to the internet—traced humanity’s evolving need to connect, charting developments from 4000 BC to the digital age. Futuristic videophones also speculated on how we might communicate in years to come. In 2000, these ideas felt fanciful. Today, they read as surprisingly restrained given how profoundly digital communication now shapes everyday life.

Money Zone: Visitors could “spend” a virtual fortune in just 60 seconds, prompting reflection on wealth and consumption. For me, the most striking exhibit was a real £1 million in £50 notes displayed behind glass. A stark reminder of society’s enduring fascination with money and spending.

Journey Zone: This architecturally daring space showcased transport innovation—from high-speed trains to space tourism—blending past achievements with present technologies and imagined possibilities. It also conveyed a sense of momentum, reinforcing the Dome’s broader belief that progress was inevitable.

Millennium Dome Exhibition: Exploring the ‘Where We Live’ Theme

This theme explored the planet we call home.

Shared Ground: Made from recycled cardboard, this zone highlighted community, responsibility, and social connection. As we moved through the space, recorded messages left by other visitors played softly—contributions intended for a time capsule. Hearing strangers speak to an unknown future reinforced the zone’s ecological message. It felt quietly hopeful, grounded in the idea that collective voices might still matter.

Living Island: A whimsical recreation of a British seaside resort with a beach, cliffs, and a lighthouse. This zone promoted environmental awareness and sustainability. Having grown up near the coast, I found the setting strangely familiar, which made its message feel even more personal.

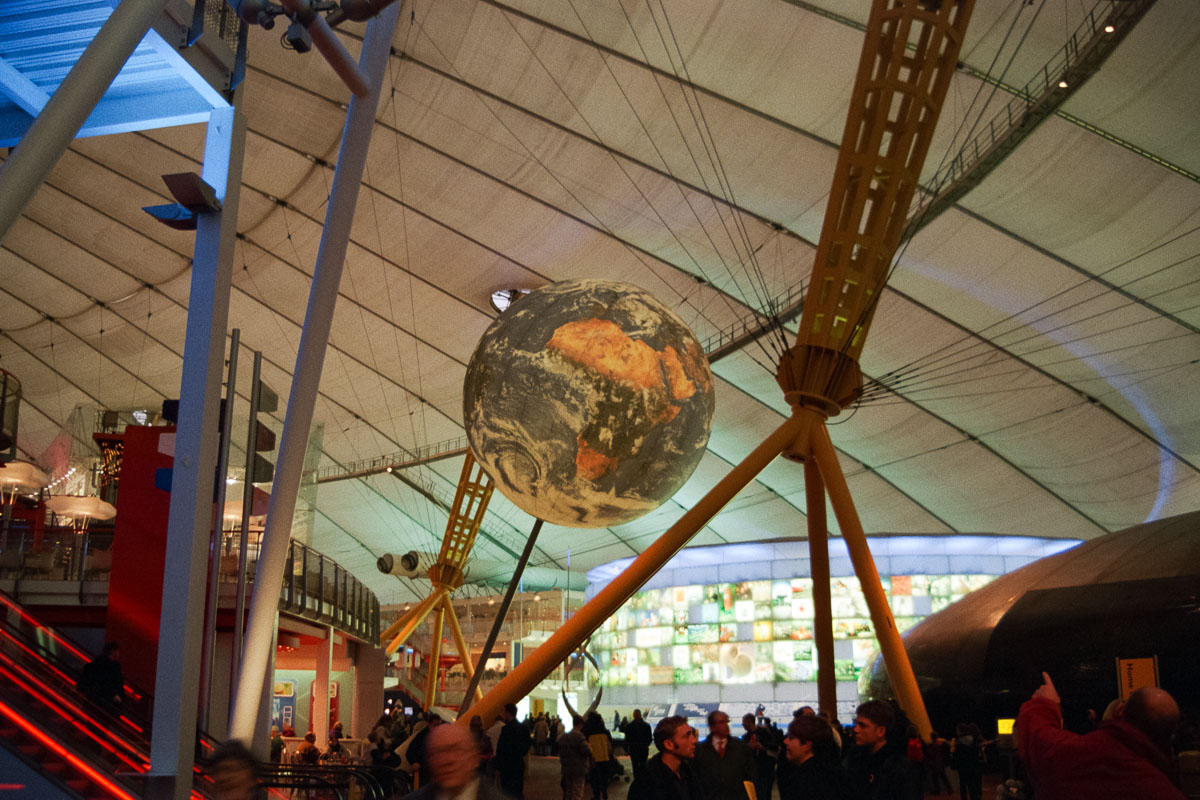

Home Planet: Guided by animated aliens, visitors embarked on a simulated journey through inner and outer space, exploring Earth’s place in the universe. It was an enthralling experience, and I remember feeling strangely small yet connected. Nearby, a 12-metre model of Earth hovered as a central landmark, drawing visitors back again and again.

Inside the Dome: Other Attractions

These exhibits contributed to the exhibition’s overarching theme: celebrating everyday life in Britain in 2000.

Timekeepers of the Millennium: This futuristic exhibit explored the concept of time with guides, Coggs and Sprinx. Behind the Stonehenge entrance, it displayed objects collected on their travels, such as Da Vinci’s flying bicycle. As someone who once researched the neural mechanisms of time, I found the space both entertaining and oddly resonant.

The Millennium Show: A stunning aerial performance by gymnasts, dancers, and actors, set to music by Peter Gabriel. The show told a Romeo & Juliet-inspired love story, played out in the central arena beneath the Dome’s roof. In essence, it was part theatre, part circus, and pure spectacle. I remember being captivated by the aerial acrobatics and theatrical storytelling—an unforgettable highlight of the Dome experience.

Our Town Stage: A nationwide project that brought together hundreds of local communities for grassroots performances beneath a spiky pink canopy.

Skyscape: A cinema by day—screening British comedies like Blackadder—and a concert venue by night, Skyscape offered a glimpse of what the Millennium Dome would later become. Namely, the O₂, one of the UK’s major entertainment destinations. So, if you’ve visited the O₂, you’ve stood beneath the same white canopy that once housed the original Millennium Dome exhibition in 2000.

What These Photos Reveal

These images are less about the exhibits and more about the Dome’s bold ambition: to promote Britain at the turn of the century. In 2000, the Dome felt like a snapshot of national optimism, ambition, and belief in progress.

For me, it remains an architectural wonder and a symbol of that moment in British history. Its futuristic design and engineering still spark the imagination, and the way we remember the Dome—whether positively or negatively—has become part of our shared national story.

Challenges in Inclusive Representation

Looking back, the criticisms aimed at the Dome feel more understandable. The public struggled to connect with the “Cool Britannia” campaign because it felt London-centric and dismissive of regional concerns. The Dome’s Faith Zone faced a similar challenge: representing the UK’s religious diversity in a single space was always going to be difficult.

Research into the Faith Zone suggests that, despite its intentions, some religious groups felt underrepresented or misrepresented. The same tension was evident in the Self-Portrait Zone, which aimed to capture British identity. But struggled to reconcile the country’s many diverse and often conflicting identities.

In short, the Dome was designed as a shared space to foster a sense of belonging. But the UK’s cultural complexity made that goal difficult. Yet the building’s story didn’t end there. After the exhibition closed, the Dome evolved into the O₂. Still a shared space, but now a world-class entertainment venue for everyone.

Legacy of the Millennium Dome

The Millennium Dome exhibition was expensive, divisive, and dismissed by many as a London-centric vanity project. Yet it was also inspiring. For some, it remains a symbol of government hubris; for others, it is a time capsule of national pride.

Twenty-five years on, the Dome’s significance lies less in what it delivered and more in what it attempted to accomplish: to unite the nation, celebrate a new era, and present a forward-looking vision of British identity. Its story reminds us that national projects can fail in execution yet still succeed in ambition.

Today, the Millennium Dome is no longer an exhibition. But it lives on as a repurposed icon, evolving with the country it once sought to define.

PHOTO DETAILS

Location: Millennium Dome, Greenwich, London

Date: January 14, 2000

Camera: Pentax MZ-50 (35mm SLR)

Film: Konica Centuria 200 (35mm colour film)

Scan: Minolta DiMAGE Scan Elite 5400 using VueScan software

If this post evokes memories or sparks curiosity, feel free to share or leave a comment below. I’d love to hear what the Millennium Dome exhibition meant to you.

16 Comments

We were there in May of 2000 visiting from the U.S. loved it! Great pics! Also remember Mr. Bean movie, the girl that came out of the screen and lighting up the next room with a wand and going through the Nose in the body.

Thanks, Dave for sharing your memories of the Dome. It’s a pity the place wasn’t more popular, although it is today now it’s a major music venue. Take care. P.

By Post Author

I don’t recall a scene like that in the Mr Bean movie. Are you sure you’re not misremembering? Would love to see the scene you are referring to.

I recently listened to the podcast version of this Guardian article: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2020/mar/12/millennium-dome-experience-disaster-inside-story-new-labour.

I was then so curious to see photos of the Dome in 2000 and found these pictures fascinating. Thank you for sharing them as well as your commentary.

Thank you Joanna for taking the time to comment. Take care.

By Post Author

These are so interesting to see!! 🙂

Thank you, Sam.

By Post Author

Thank you so very much for posting these pictures. I am so delighted to have come across them.

They have evoked many happy memories of two visits, when my son was 6 years old… (Now 30 !)

Sadly both my camera and video recorder, decided to ‘play up’ on both visits, so unfortunately, I have very little material to remind my son, of a very magical time.

Regards and again thanks.

Thanks, Laureen, for writing and for sharing your story. It’s amazing how photos can transport us back in time. I’m glad my pictures could help remind you (and your son) of your trips together. Take care, Paul.

By Post Author

We went to the dome in 2000 and wrote a message which was put into a capsule. They said they would be reopened in 50 years time. Do you know if this is still happening?

Hi Susan,

Thanks for dropping by. I’m not sure if the time capsule is still set to be reopened in 50 years—there’s some talk online about it possibly being disturbed by construction.

Best,

Paul

By Post Author

Hi Paul, loved your talk on C20 society this evening. I visited the dome aged 12, and have fond memories of it. I visited it 25 years ago this week, ironically. The show in the middle was the best bit, but I also liked the Human Body and Living Island Beach. Timekeepers of the Millennium was also a great play area. Your talk this evening and photos have made me feel nostalgic! Great times. I still have my Millennium Coin and Millennium Dome model.

My parents bought my ticket as a Christmas present, 1999. I remember the ticket was printed on a lottery ticket. (You could buy them from lottery terminals). I was really excited and remembered the date, 4th March 2000 I went.

The Millennium Dome was a success, in my opinion. It would be great if the O2 Arena did something to mark the 25th anniversary of the Millennium Experience.

Thanks so much for your comment, Neil! I’m really glad you enjoyed the talk and that it brought back such great memories. I agree—the Millennium Experience was a success and enjoyed by many, and it would be wonderful if the O2 marked the anniversary. Thanks again! Paul

By Post Author

My family made at least 3 trips to the dome as there was so much to see in one day. memorable moments were the acrobats high up and a brilliant show. only regret was not getting the DVD of the show as would love to see again. lovely photos from you also bring back memories. Thank You

Thanks for sharing your memories — I recently bought some memorabilia on eBay. I agree, the acrobats and show were unforgettable. Maybe you’ll find the DVD online!

By Post Author

Thank you so much to the person who shared their memory of working in the BT Talk Zone at the Millennium Dome. Apologies for accidentally deleting your original comment—I really appreciate you taking the time to share your memories!