A house with peeling wallpaper. A rusted car overtaken by weeds. A factory frozen in time. At first glance, abandoned places may seem empty. Yet these spaces evoke powerful emotions and connections. But why do we feel such a pull toward these forgotten spaces? The answer lies in the idea of place attachment. Thus, this post explores the psychological roots of place attachment and explains how abandoned places influence who we are.

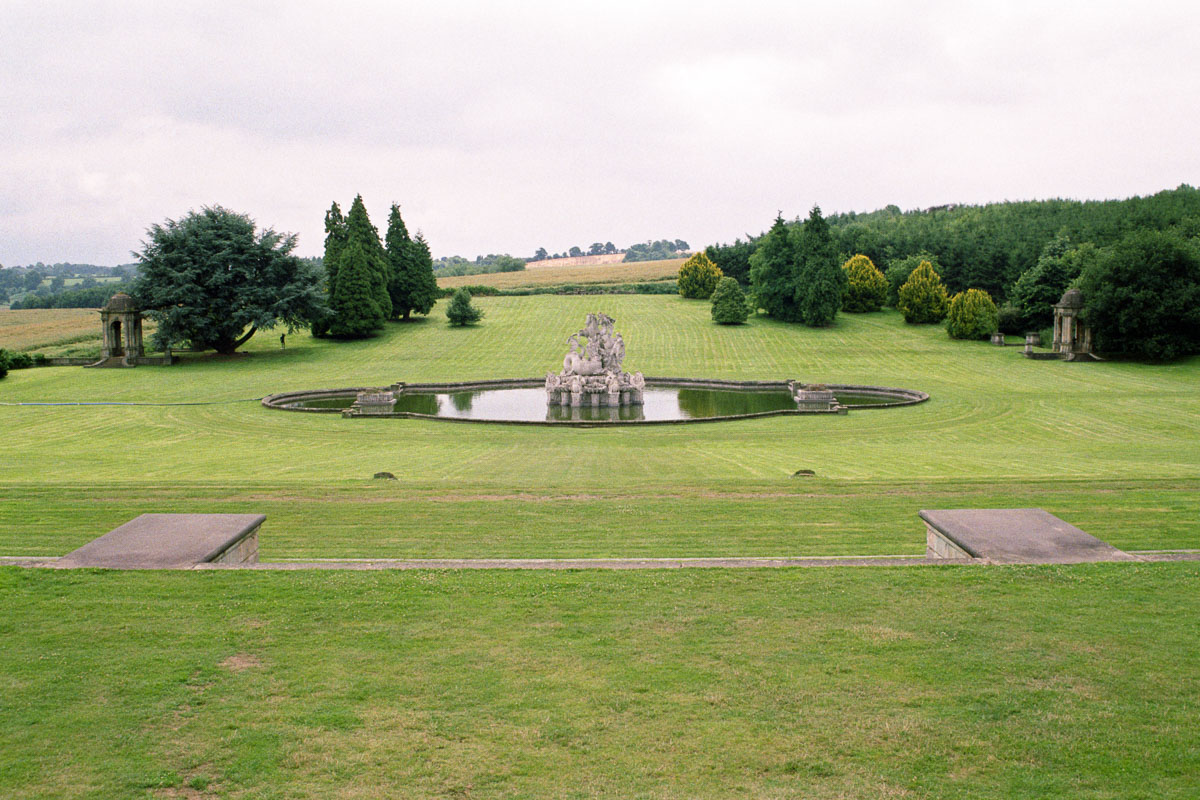

Note: The photos featured in this post show Witley Court when it was left to ruin. I’ve included them to illustrate the haunting beauty of abandonment photography.

Understanding Place Attachment: A Psychological Perspective

Place attachment is the emotional bond or connection people develop with specific locations through experience, memory, and shared meaning. Psychologist Maria Lewicka (2011) explains that such connections become part of who we are, influencing how we see ourselves and where we feel we belong. Place attachment is not just about physical space—it’s about the feelings, memories, and cultural significance that tie us to a place, shaping our identity over time. For instance, a boarded-up childhood home isn’t just a building—it symbolises formative experiences, personal growth, and a sense of belonging.

Six Ways Place Attachment Shapes Identity Through Abandoned Places

Even in decay, abandoned places profoundly affect our sense of self. Here are six ways this happens, with examples:

1. Memory and Nostalgia Reinforce Personal Identity

Nostalgia isn’t just a sentimental longing for the past—it’s a psychological mechanism that helps maintain a sense of continuity in our sense of self or personal identity (Sedikides et al., 2016). Abandoned places often prompt this emotional reflection, connecting us to a version of ourselves that no longer exists but still shapes who we are.

Example: Returning to a shuttered seaside amusement park may remind us of youthful excitement, offering insight into how we’ve changed.

2. Collective Memory Grounds Cultural Identity

While personal memories help anchor our identity, abandoned places contribute to a broader sense of belonging. Sociologists like Pierre Nora (1989) argue that abandoned places function as lieux de mémoire—sites of memory that preserve cultural identity. Even in decay, for instance, these spaces hold cultural meaning, connecting people across generations and shaping group identity.

Example: A disused colliery may still represent a town’s industrial heritage and shared resilience.

3. Mental Maps Preserve Sense of Place and Self

As collective memory anchors cultural identity, our internal sense of place also helps preserve our identity, even when the environment has changed. Indeed, urban planner Kevin Lynch (1960) argued in The Image of the City that people navigate cities through mental maps built from landmarks and paths. Abandoned sites often remain part of these inner landscapes, shaping how we remember and interpret our environments.

Example: A derelict skate park might no longer exist, but it remains vivid in the memory maps of those who spent their formative years there.

4. Emotional Atmospheres Evoke Reflection and Meaning

Beyond how we navigate space, abandoned places also shape how we feel. For example, Psychogeography, developed by Guy Debord and expanded by writers like Iain Sinclair, explores how spaces affect our emotions and behaviour. In this context, abandoned places as affective atmospheres offer fertile ground for reflection, often evoking melancholy or curiosity, shaped by light, texture, and sound.

Example: Walking through a disused underground station can provoke existential reflection—what once bustled with life now lies eerily still, prompting thoughts about time and change.

5. Loss of Social “Third Places” Disrupts Community Identity

Moreover, these emotional impressions don’t just affect individuals—they ripple through communities. Sociologist Ray Oldenburg identified “third places” like cafés and libraries as essential for social connection. But when communities lose such places, the impact goes beyond function—it ruptures a shared sense of identity.

Example: An empty pub in a rural village that once hosted weddings and wakes. Its silence now reflects how local life has fragmented.

6. Counter-Spaces Enable Alternative Identities

Beyond the fragility of community identity, abandoned sites often become spaces of resistance and reinvention. Tim Edensor (2005) argues that urban ruins challenge the dominant social order. Unlike polished, regulated spaces, these “in-between” places invite freedom, creativity, and alternative identities, particularly for those on the margins.

Example: A graffiti-covered warehouse may become a refuge for artists or skaters, symbolising resistance and reinvention.

7. Postmemory Extends Place Attachment Across Generations

While abandoned places can inspire awe and alternative identities, they also carry inherited memories that connect us to histories beyond our own experience. Cultural theorist Marianne Hirsch’s concept of postmemory explains how people can feel connected to events or places they never experienced, through inherited stories or media. Consequently, abandoned places can carry these emotional echoes across generations.

Example: A young person may feel a deep bond with a family home in another country, even if they’ve only seen it in photographs and stories.

The Vital Role of Photography in Preserving Place Attachment

All these layers of memory, emotion, identity, and community that abandoned places evoke risk fading away as physical sites decay or disappear, which is why photography plays a vital role by capturing and preserving their emotional and historical meaning. As Susan Sontag (1977) noted, photographs fix what might otherwise fade, allowing stories and attachments to survive beyond physical decay. Thus, a photo of a crumbling pier does more than document deterioration—it preserves cultural significance and keeps the place’s identity alive.

Key Points: How Place Attachment Shapes Identity Through Abandoned Places

- Memory and Nostalgia: Anchor personal identity over time.

- Collective Memory: Root cultural and group identities.

- Mental Maps: Influence spatial understanding and self-location.

- Emotional Atmospheres: Encourage reflection and deepen meaning.

- Community Loss: Alters social identity and belonging.

- Counter-Spaces: Foster alternative identities and creativity.

- Postmemory: Passes place-based identity across generations.

- Photography: Preserves and communicates place attachment and identity.

Conclusion

In short, place attachment to abandoned places plays a vital role in shaping personal and collective identity. Through memories, cultural meaning, and emotional experiences, these forgotten spaces continue to influence how we see ourselves and our communities. Finally, recognising the importance of place attachment in abandonment photography enriches our understanding of identity, reminding us that even in decay, places remain powerful mirrors of who we are.

Discover how exploring abandoned places can restore focus, creativity, and calm — read my full post: How Urbex Photography Helps Mental Health and Creativity.

Join the Conversation

Do abandoned places spark memories or feelings? Share your thoughts below!

If this post resonated with you, please like, share, and explore my other abandonment photography posts.